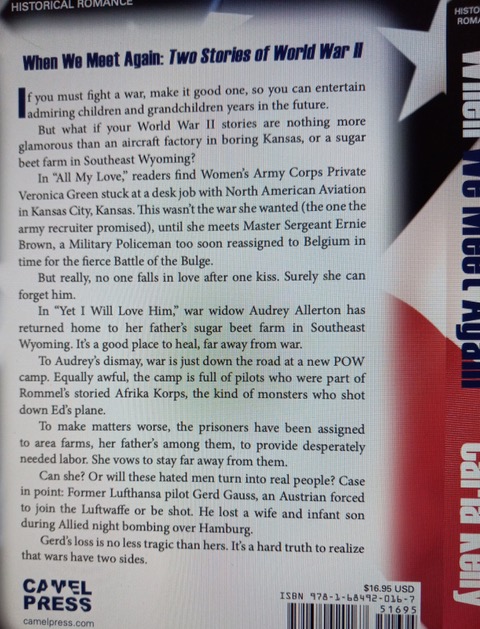

I know, I know. I’ve written way too many books to get excited about this next one out of the chute on October 11. But I am excited and can’t wait to get my hands on that book. When We Meet Again represents the first time I have written about midcentury events, World War II this time. It’s two lengthy stories, rather than one novel.

For several years, I’ve been researching another WWII story and will probably write it next year. What this has done for my research is fill my bookshelves with all manner of 1940s stuff.

Who am I kidding? I’ve studied WWII my whole life and I have the books to prove it. Books and war stories, some close to home, have been part of my life since forever, mainly because my parents were both veterans of the U.S. Navy during the war. Dad made the Navy his career, and we were lucky to be a Navy family. No regrets.

Go Navy. Curiously enough, “All My Love” is an Army story, set in glamorous Kansas City, Kansas, at North American Aviation, one of several major facilities where the Mitchell medium-range bomber was built. My heroine, Private Veronica Green, listened to the siren call of an Army recruiter promising her, as a WAC, an exotic posting to Great Britain, or maybe even France eventually. From post-Dust Bowl Oklahoma, she finds herself in a neighboring state for her war. For a brief time, it’s also Master Sergeant Ernie Brown’s war, until he ends up in Europe back in the thick of it.

But that’s life, isn’t it? We plan and contrive and hope and dream, and we end up in Kansas. What Ronnie makes of “her war” is what we all make of the hand Fate deals us, eh? This story is also a salute to the GI Bill, one of America’s greatest ideas, right up there with our national park system and Head Start.

On a deeply personal note, I named this “All My Love,” after the way Harold Seuss, a Navy SeaBee, used to sign all the letters he wrote me during the Vietnam War. He happened to be in Da Nang during the Tet Offensive in 1968, which meant I worried about him all the time. As that long year wore on, I ended up writing him every day. When he returned, I met him in Salt Lake City before he flew home to Missouri. The second thing he did was thank me for all those letters. He told me, “I knew that no matter what happened, I would always get a stack of letters at Mail Call.”

I only wish he were alive today to know that I used the idea of those letters in a story. Thanks, Harold. You were one of the good guys. I guess I’ll always miss you.

The second story, “Yet I Will Love Him,” is set in equally glamorous Goshen County, Wyoming, where there used to be a German POW Camp. Audrey Allerton’s story is about what happens when a war widow returns home to her father’s farm to heal from the loss of her three-month husband, killed when his plane is shot down into the English Channel by a Messerschmitt 109, no body recovered.

Audrey is not prepared for the unwelcome news that her father, among other farmers, is using PWs – the term then – to help with the planting, weeding, and harvest of beans, for which they are paid a small wage, and treated according to Geneva Convention standards.

She can’t avoid the hated Germans, many of whom are pilots. She learns a painful home-truth: Once you get to know the enemy, you might, just might, learn that they are human, too. Mourning her great loss, she discovers that Feldwebel Gerd Gauss, North African prisoner from Rommel’s storied Afrika Korps, knows great loss, as well.

“Yet I Will Love Him” was a story I knew I would eventually write someday. When we lived in Torrington, Wyoming, I was a ranger at Fort Laramie National Historic Site. One of my collateral duties was to serve as the site’s liaison with the Goshen County Historical Society. This meant I attended the society’s monthly meetings and found ways to help out with their projects, as requested.

One evening after the meeting, I chatted with an older lady about that long-gone PW camp. She told me her story: One day as she was driving, a policeman stopped traffic so a string of newly arrived prisoners of war could walk from the railroad depot to the armory across the highway, and then to the camp.

It must have been near the end of the war, when Germany was scraping the bottom of the barrel for soldaten to replace the many dead. I never forgot what she told me. “They were so young!” she said. “I sat there in my car and cried.” I still remember that stricken look in her eyes. I imagine she was thinking of her own sons away at war. She was remembering her war.

Anyway, I never forgot it. “Yet I Will Love Him” is a direct result, forty-seven years later, of that memory. In the same way, “All My Love” is my homage to a friend and honoring his friendship the only way I could, by seeing that he never had a mail call without a letter. I still have Harold’s letters.

I owe my thanks to reader Arsula Shumway. Before I began this, I asked my Facebook friends if they had any World War II stories of how their parents met. I got a whole bunch of wonderful stories, and selected only the smallest part of one. Arsula introduced me to her parents Veronica Green and Ernest Brown, U.S. Army Military Police, who met on a Greyhound bus. I took that meeting and ran with it. What follows is strictly mine, but it wouldn’t have happened if Arsula hadn’t mentioned that bus…

-CK