Think what you will, but during the pandemic, I did something that brought me a lot of comfort: I reread many of my novels.

Through the years, I’ve reread a few of my own personal favorites. At times, I’ve been asked to speak about a particular book, which means rereading at least parts of one so I can sound reasonably coherent upon demand.

I haven’t reread all of them, but I discovered something interesting: I had forgotten enough to make the reading enjoyable.

You might be asking yourself, “This woman is a nitwit. How can she possibly forget something she wrote?” It’s easier than you think.

Many years ago, I had the good fortune to attend A.C. Jones High School in Beeville, Texas. As a freshman, I gravitated toward journalism and the school newspaper, which turned out to be no ordinary newspaper.

We were exceptional, because we had an exceptional teacher, Jean Dugat, who believed in training exceptional writers. She was exacting and demanding and precise, and by golly, we had to know our stuff. We did. By my senior year, I was one of two associate editors. My principal stewardship was feature writing, those articles with sizzle. (As opposed to ”Gimme the facts, ma’am,” although I have since discovered historical fiction, with both facts and sizzle.)

When we wrote our articles, we counted the inches of copy. The goal was to reach one thousand inches. Words and more words. I think about those thousand inches, and wonder how many words I’ve written since I was a high school sophomore. It’s well into the millions.

Much earlier in my writing life, I assured myself that I would never forget anything I ever wrote. I have forgotten stuff I really wanted to remember. What this means is that rereading my own novels and short stories has been huge fun.

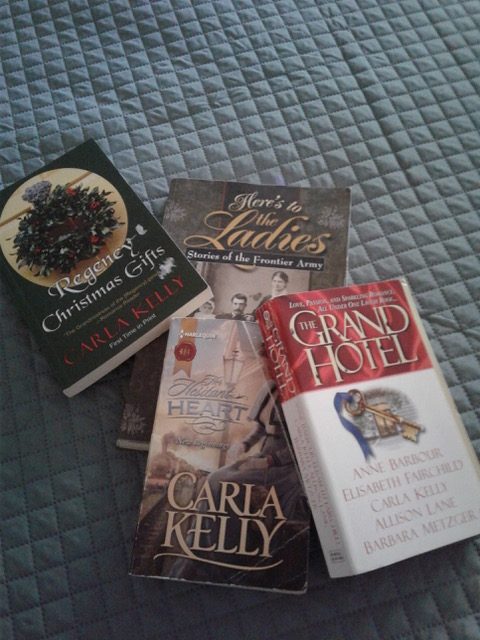

There are some things I never forgot. I remember one perfect sentence in a short story titled, “The Background Man.” It’s in an anthology called The Grand Hotel, the premise being that each of the five stories circles around this new hotel opening during that delirious summer when Napoleon was finally imprisoned on distant St. Helena and London celebrated peace after a generation of war.

The background man is a quiet fellow who is the manager of the Grand Hotel. He takes Miss Carrington, one of the guests, to see the Elgin Marbles, temporarily housed in a shed. She’s been sketching the marbles, and he surprises himself by kissing her. To his amazement, she returns his affections.

Here’s the sentence: “As he sat beside her, still so close, she picked up the sketch pad, and with fingers that shook a little, drew his own face. Surrounded by wonders of the ancient world, she drew his face.”

Simple, and perfectly right. Millions of words, and I remember those two sentences. It happened again in “Mary Murphy,” a short story in Here’s to the Ladies: Stories of the Frontier Army. It’s been anthologized elsewhere, too. I wrote it in 1977, and it was among my first published works.

But dagnabbit, I was never happy with that final paragraph, told from the point of view of a retired army officer looking back on an event from years earlier, when, as a lowly second lieutenant, he came up woefully short. That last sentence, the one that matters, involved something about the company laundress doing well, and her children were probably strong like her. Too sappy. Not right. Oh well. It sold.

In 2003, those early Fort Laramie stories were collected into Here’s to the Ladies, and published by Texas Christian University Press. Still despairing over that last sentence, I dragged out the story again and reread it. Bam, just like that, I knew what to do. After 26 years of stewing over that ending, I knew. Now it reads, “Well, never mind. Mary Murphy. I think of her.” Nine words, twenty-seven years, and I finally got it right. Spoiler alert: Finally, the last four words express what the story hints at – across the unbridgeable gap separating officers and common army folk, he loved that woman.

I also remember meaningful passages that don’t take twenty-seven years to speak to me. One is in Her Hesitant Heart, a favorite book of mine set at Fort Laramie in 1876. The protagonist, Susanna Hopkins, has left an abusive husband behind in Pennsylvania and suffered through a divorce that separated her from her young son. It was an era when women never won those disputes.

With the help of an odd fellow named Nick Martin, Tommy Hopkins finds his mother in Cheyenne. They have both suffered and the boy has a major regret. “She dried her son’s tears with her apron, and put her hands on each side of his head, capturing his attention in her gentle way. ‘Tommy, I have learned something you need to know. It’s very important, so heed me. Sometimes the only person you can save is yourself. This was one of those times.’

“She hugged him, soothed him, sang him to sleep and tucked the covers around him as Joe marveled at the strength of women and the resiliency of children.”

During the pandemic, I found my own strength in rereading some of my books. I just finished rereading Regency Christmas Gifts, a three-story Christmas anthology I wrote in 2015. I love each of the three stories. For “Lucy’s Bang-up Christmas,” I let Lucinda Danforth borrow my own personal solace from scripture, because she needed it. Her mother has died a few months previously, her older sister is getting married on Christmas Eve, and there isn’t time to celebrate her mother’s favorite season because of the wedding.

Lucy is determined to honor her mother’s memory and find a way to squeeze in the holiday rituals. She admits to her second cousin, Miles Bledsoe, how she copes. He cuddles her a little, then this:

“She sat up finally, and flashed him a faintly embarrassed smile. “So sorry! When I feel melancholy, I read Mama’s underlined verses. And lately, I’ve added some of my own.

“Tell me one,” he said.

“It’s in Micah.” She must have noticed his expression. “Miles, Micah is in the Old Testament. Please tell me you have heard of the Old Testament.

“I have,” he said, suddenly not wanting to disappoint this new Lucinda Danforth.

“This part: ‘When I fall, I shall arise; when I sit in darkness, the Lord shall be a light unto me.’

“She gave him a sweet look, with no mischief in it. “It really does work.”

During this extra-long year of distress and loss for many, and inconvenient for all of us, I’ve been rereading Micah. Lucy is right. It really does work.

That is one way this writer copes. I’m glad I write.